The global conversation around education policy has historically been dominated by a single metric: access. For decades, the primary objective of governments and multilateral organizations was to build more schools, train more teachers, and get more bodies into classrooms. However, the release of the OECD Education Policy Outlook 2025 this December marks a profound shift in this narrative. The report, titled “Nurturing Engaged and Resilient Lifelong Learners in a World of Digital Transformation,” declares that the era of “access-first” policy is over. In its place, the OECD introduces a nuanced, psychological, and structural framework designed to solve a more persistent problem: the stagnation of human potential in an age of rapid change.

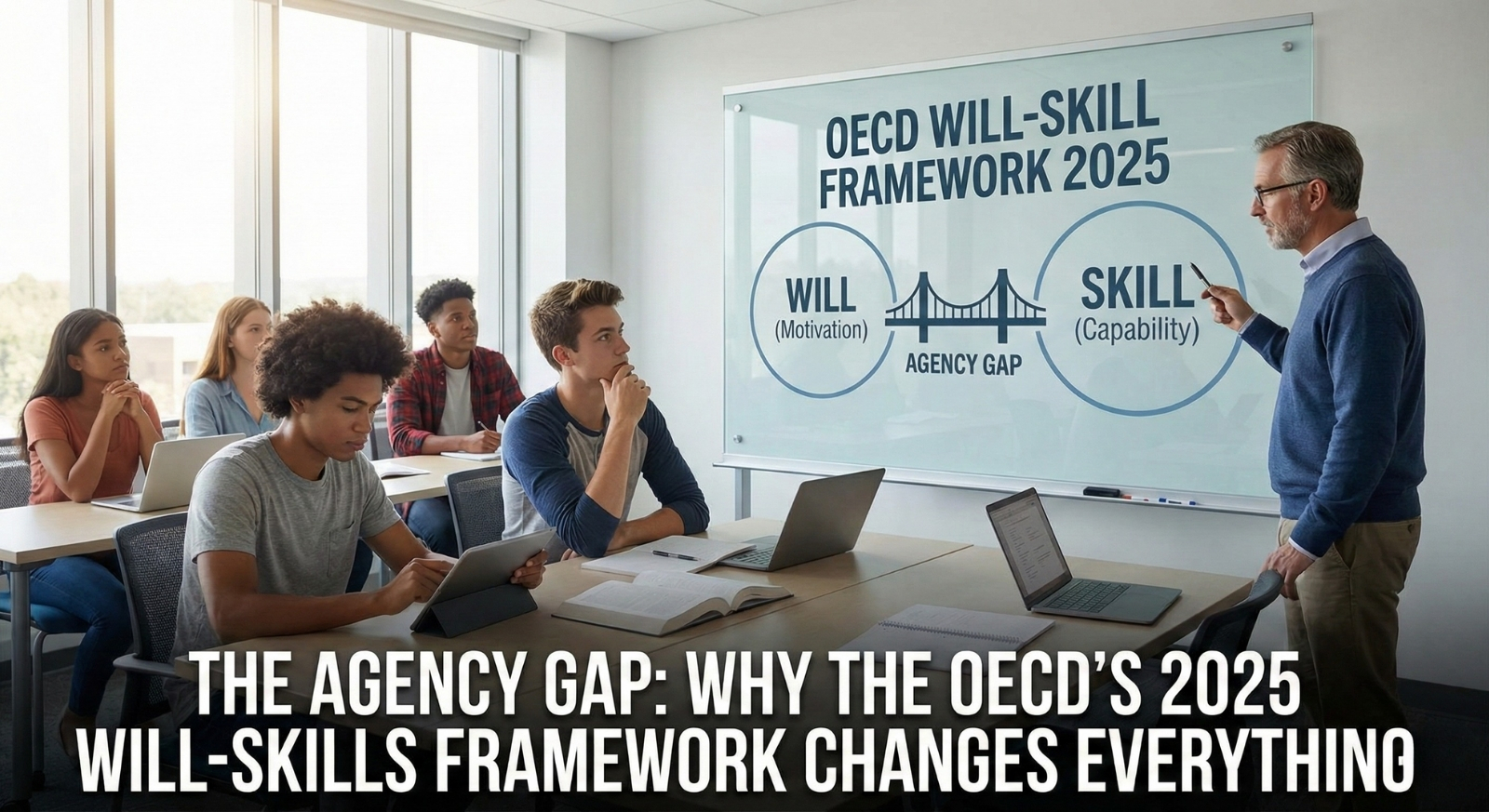

The core finding of the 2025 Outlook is stark. Despite massive investments in educational infrastructure and digital tools, adult learning participation rates across the developed world have plateaued. Even more concerning, foundational skills in literacy and numeracy are declining or stagnating in several advanced economies. The report argues that simply providing the opportunity to learn is no longer sufficient if individuals lack the agency to seize it. To address this, the OECD has introduced the “Will, Skills, Means” framework—a triad of dependencies that is set to redefine how nations design their human capital strategies.

The Framework: Will, Skills, and Means

The “Will, Skills, Means” model posits that successful lifelong learning requires the simultaneous presence of three distinct factors. If any one of these is missing, the system fails.

1. The Will: The Psychological Engine

The “Will” represents the internal engine of the learner. It comprises curiosity, confidence, motivation, and socio-emotional resilience. The report highlights that many adults fail to engage in upskilling not because programs aren’t available, but because they lack the “learner identity”—the belief that they are capable of acquiring new skills. This is particularly acute in populations that had negative experiences with formal schooling in childhood. The policy implication is massive: governments must stop funding “training” and start funding “engagement.” This means investing in outreach, career guidance, and psychological support that helps individuals see the value of learning.

2. The Skills: The Cognitive Toolkit

The “Skills” component refers to the foundational capabilities required to learn effectively. In 2025, this goes beyond reading and writing to include “transversal competencies” like adaptive problem-solving and digital literacy. The OECD Skills Outlook 2025 reveals a troubling “Matthew Effect” in skills accumulation: those who already have high skills (often from tertiary-educated parents) acquire more skills, while those with low skills fall further behind. For example, adults with tertiary-educated parents score half a standard deviation higher in core skills than their peers. Without these foundational skills, an individual cannot navigate the complex digital learning platforms that are supposed to democratize education.

3. The Means: The Structural Enablers

Finally, the “Means” addresses the logistical barriers: time, money, and networks. The report identifies that for mid-career adults, the “cost” of learning is often measured in time rather than tuition. The “Means” are the resources that make participation possible. The report praises initiatives that provide paid training leave or flexible, modular micro-credentials, which allow learners to fit education into complex lives.

Critical Life Moments: A New Temporal Strategy

The report applies this framework across four “critical life moments,” suggesting that policy interventions must be timed to coincide with periods of high developmental plasticity or high risk.

Early Childhood (Ages 0-6): The Foundation of Curiosity

The report identifies early childhood not merely as a time for care, but as the critical window for establishing the “Will” to learn. Policies in countries like Czechia and Spain are highlighted for expanding access to high-quality Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) for children aged 0-3. The report argues that the quality of the workforce is paramount here; educators need professional development to create environments that foster curiosity rather than just compliance.

Adolescence (Ages 10-16): Identity and Purpose

In adolescence, the focus shifts to “Shaping Identity and Purpose.” The OECD warns that high-stakes testing regimes can crush learner agency during this volatile period. Instead, successful systems nurture the “Will” by making learning “relevant, relational, and purposeful.” Positive teacher-student relationships are identified as the single strongest predictor of continued engagement.

Mid-Career: Breaking the Stagnation

For adults, the challenge is breaking the “skills trap.” The Skills Outlook 2025 notes that women are more likely to engage in communication and language training, while men dominate technical and machinery-related training. This gender segregation limits workforce adaptability. Policies must target the “Means” by subsidizing training that crosses these traditional divides.

Conclusion: The Agency Imperative

The OECD’s 2025 analysis is a call to action for a more human-centric approach to policy. It challenges governments to look beyond the “hardware” of schools and computers to the “software” of human motivation and agency. As automation reconfigures the labor market, the nations that succeed will not necessarily be those with the most university graduates, but those with the most resilient, adaptable, and self-motivated learners.

Good article!